During past decades, the percentage of patients with multiple comorbidities, as well as complex coronary artery disease (CAD) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), has increased.1 With prevalence rates of AF reaching 1–3% of the general population, it comes as no surprise that up to 7.1% of patients undergoing PCI have AF.2–4 Thus, the probability of a patient undergoing complex PCI while requiring oral anticoagulation (OAC) is not negligible. Although there is not a universally adopted definition, complex PCI usually refers to procedures with implantation of three or more stents, treatment of three or more lesions, bifurcation with two stents implanted, total stent length >60 mm, or treatment of a chronic total occlusion.5 Complex PCI patients are at an increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events, MI, stent thrombosis (ST), and ischemia-driven revascularization, while they also have a greater risk for major bleeding complications compared with non-complex PCI patients.6

In contrast, patients with AF are at an increased risk for thromboembolic and bleeding events due to the prothrombotic milieu of AF, as well as concurrent anticoagulation therapy.7 Therapeutic management of such patients in everyday clinical practice represents a challenge for clinicians, as the combination of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy, to mitigate ischemic and thromboembolic events associated with stent implantation and AF, comes at the cost of an increased risk for major bleeding.

Triple antithrombotic therapy (TAT), consisting of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) plus an OAC agent, was until recently the treatment strategy of choice for AF patients undergoing PCI with stent implantation.8 However, emerging evidence points to the superiority of dual antithrombotic therapy (DAT), consisting of a single antiplatelet agent and OAC, regarding safety outcomes, without significantly compromising efficacy, although there is some concern regarding the risk of ST.9–11 Taking into account that such a risk is even higher in patients undergoing complex PCI compared with those undergoing non-complex PCI, the efficacy of DAT may be a more complex issue.

Triple Antithrombotic Therapy or Dual Antithrombotic Therapy?

Data regarding the optimal antithrombotic strategy in complex PCI patients with an indication for OAC are scarce. Although early hypothesis-generating data regarding the optimal post-PCI treatment scheme in patients receiving OAC were presented in the WOEST study, most evidence dedicated to AF patients undergoing complex PCI procedures comes from subgroup analyses of subsequent randomized trials, such as PIONEER AF-PCI and RE-DUAL PCI (Table 1).12–14

The PIONEER AF-PCI trial evaluated the use of rivaroxaban as part of DAT in 2,124 patients with AF undergoing PCI with stent implantation. Patients were randomized to receive rivaroxaban (15mg once daily) plus a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor (group 1), rivaroxaban (2.5mg twice daily) plus DAPT (group 2), or TAT with a vitamin K antagonist (VKA) plus DAPT (group 3). Patients receiving DAT with rivaroxaban had lower rates of clinically significant bleeding compared with patients receiving TAT with VKA (HR 0.59; 95% CI [0.47–0.76]; p<0.001), while presenting a similar rate of ischemic events (HR 1.08; 95% CI [0.69–1.68]; p=0.75).13

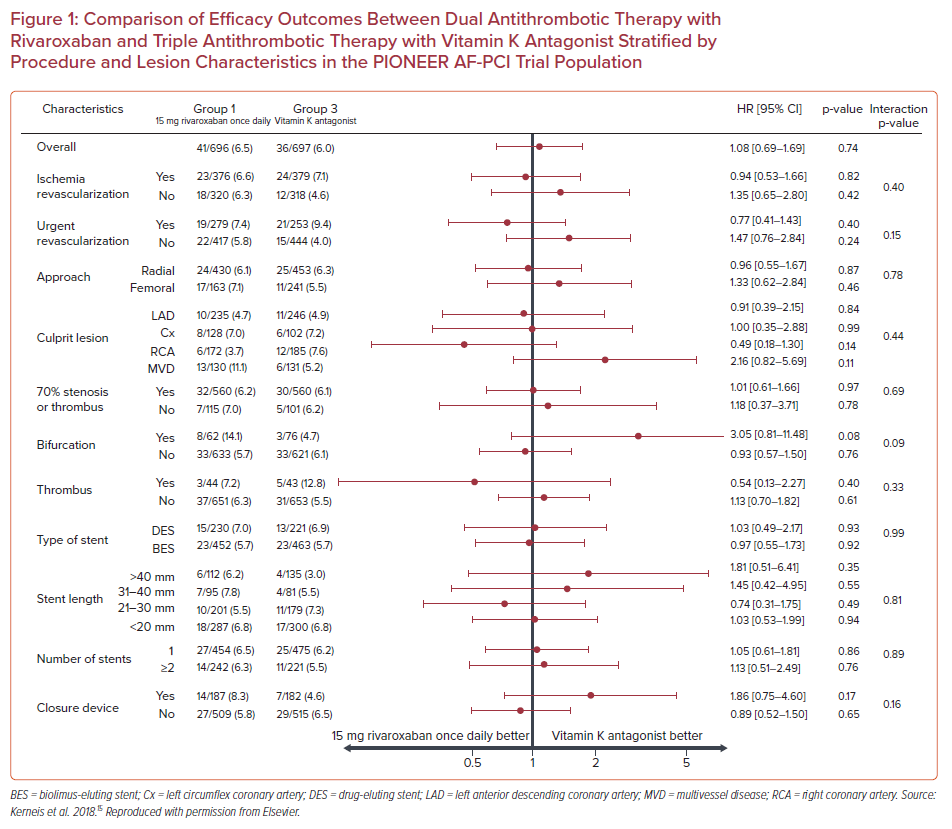

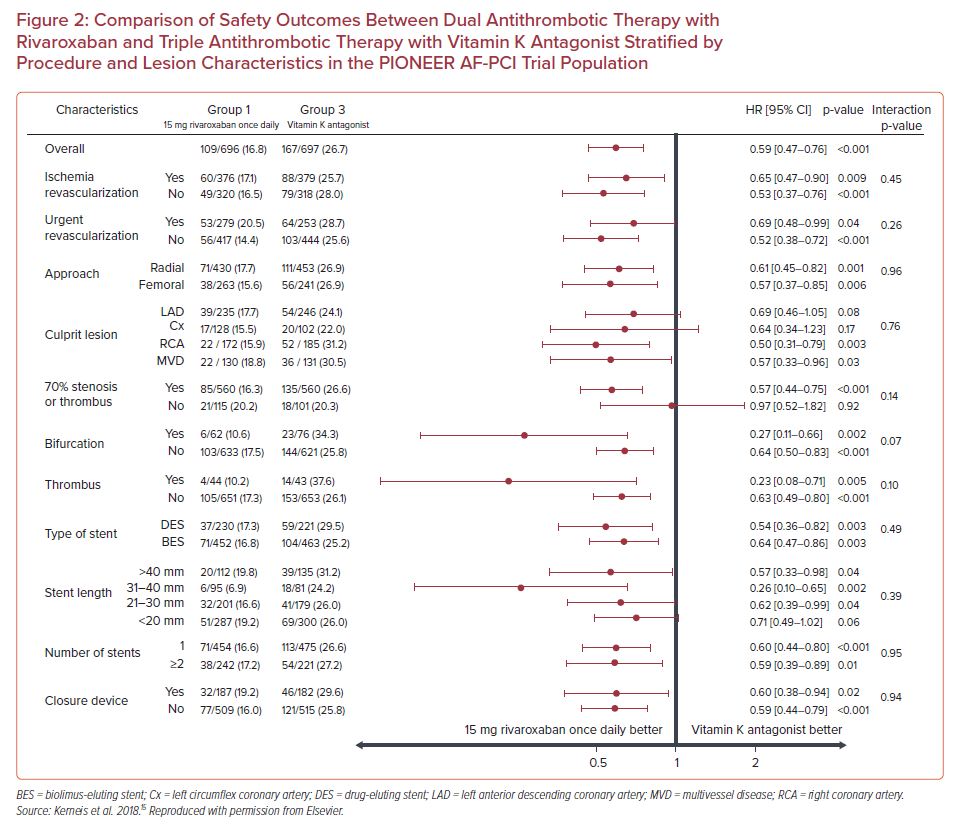

Subgroup analysis showed that the treatment effect of rivaroxaban on major adverse cardiovascular events did not vary when stratified by the location of the culprit artery, presence of a bifurcation lesion, presence of thrombus, type and length of stent, or number of stents (p for interaction>0.05 for all subgroups), reaching the conclusion that there was not an interaction between the complexity of coronary lesions and the effect of rivaroxaban on efficacy outcomes (Figure 1).15 Additionally, regarding safety outcomes, in patients with 70% stenosis or thrombus, bifurcation lesions, stent length >40 mm, or two or more stents implanted, DAT with rivaroxaban was associated with fewer bleeding events compared with TAT with VKA (HR 0.57; 95% CI [0.44–0.75]; p<0.001; HR 0.27; 95% CI [0.11–0.66], p=0.002; HR 0.57; 95% CI [0.33–0.98]; p=0.04; and HR 0.59; 95% CI [0.39 –0.89]; p=0.01, respectively; Figure 2). In brief, there was no effect modification by the presence of complex coronary lesions on the results of either bleeding or efficacy endpoints evaluated in the PIONEER AF-PCI trial.

The RE-DUAL PCI trial recruited 2,725 patients with AF who had undergone PCI, and randomized them to receive either TAT with warfarin plus DAPT or DAT with dabigatran (110 mg or 150 mg twice daily) plus a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor. Dual therapy with dabigatran was found to be superior to triple therapy regarding bleeding events, and non-inferior regarding thromboembolic events prevention in patients with AF undergoing PCI.14

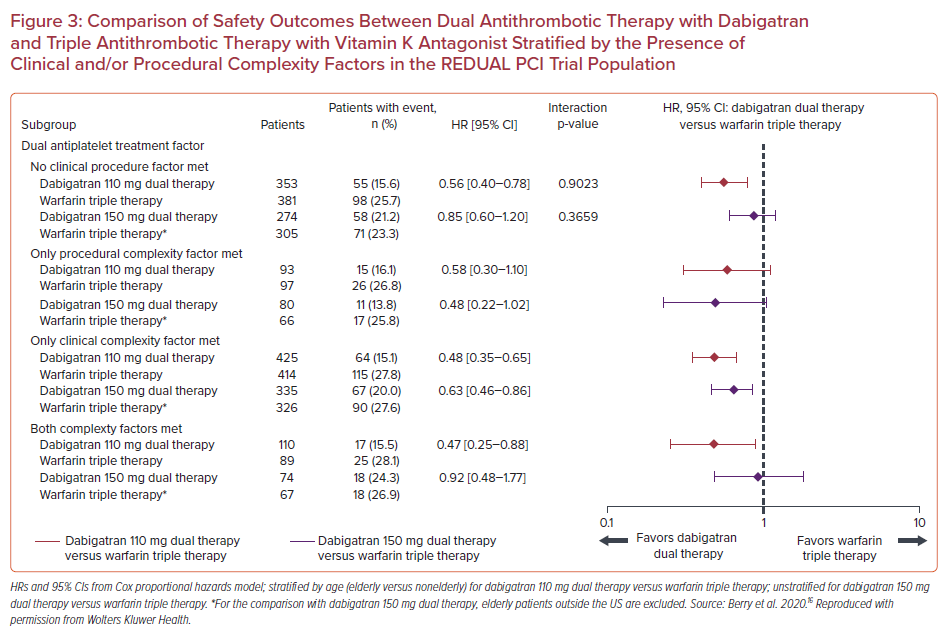

A subgroup analysis of RE-DUAL PCI trial categorized patients according to the absence or presence of clinical and/or procedural complexity factors with the view to evaluate their effect on treatment outcomes.16 In detail, procedural complexity factors included more than two vessels treated, in-stent restenosis of a drug-eluting stent, prior brachytherapy, unprotected left main, more than two lesions per vessel, lesion length ≥30 mm, bifurcation lesion with a side branch ≥2.5 mm, vein bypass graft PCI, or a thrombus-containing lesion. Clinical complexity factors included acute coronary syndrome (ACS) presentation, acute ST-elevation MI, renal insufficiency/failure, and left ventricular ejection fraction <30%. In a total of 2,725 patients, 1,008 (37.0%) had no complexity factors, 1,174 (43.1%) had clinical complexity factors, 270 (10.0%) had procedural complexity factors, and 273 (9.9%) had both clinical and procedural factors. DAT with dabigatran was associated with lower rates of the primary bleeding endpoint compared with TAT with warfarin in all categories of clinical or procedural complexity. HRs for the dabigatran 110 mg group were 0.56 (95% CI [0.40–0.78]) for no complexity factors, 0.58 (95% CI [0.30–1.10]) for procedural complexity alone, 0.48 (95% CI [0.35–0.65]) for clinical complexity alone, and 0.47 (95% CI [0.25–0.88]) for both procedural and clinical complexity factors (p for interaction=0.90). In the 150 mg group, the respective HRs were 0.85 (95% CI [0.60– 1.20]) for no complexity factors, 0.48 (95% CI [0.22–1.02]) for procedural complexity alone, 0.63 (95% CI [0.46–0.86]) for clinical complexity alone, and 0.92 (95% CI [0.48–1.77]) for both procedural and clinical complexity factors (p for interaction=0.37; Figure 3).

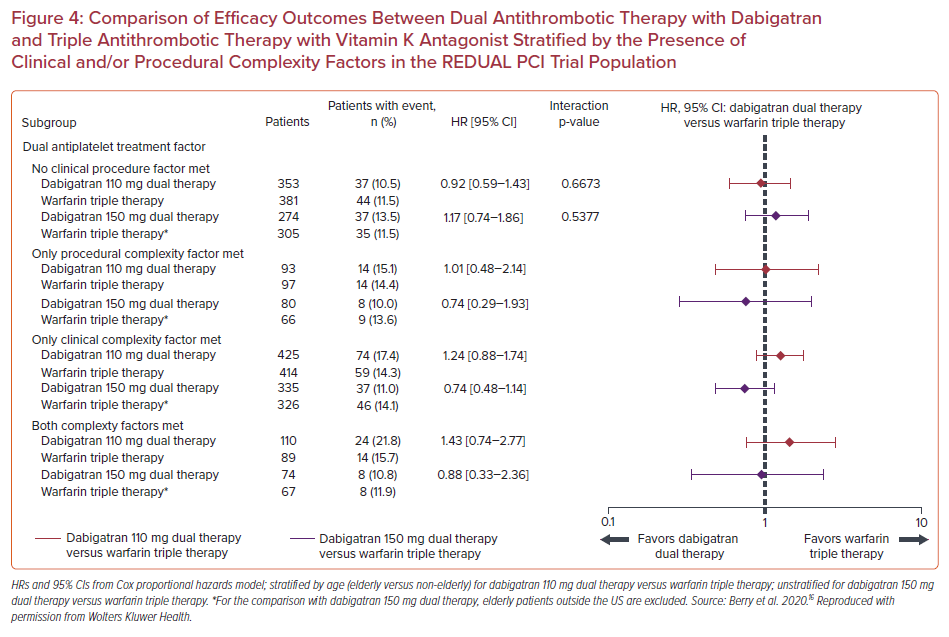

As far as efficacy outcomes are concerned, the risk of thromboembolic events seemed similar in both the dabigatran DAT groups compared with the TAT with warfarin groups, irrespective of procedural and/or clinical complexity. (p for interaction=0.67 for dabigatran 110 mg and p for interaction=0.54 for dabigatran 150 mg). ST rates were low in all groups (1.2% for patients with clinical complexity alone, 0.4% for procedural complexity alone, 1.8% for both procedural and clinical complexity, and 1.0% for no complexity factors), hindering comparison of potential subgroup differences (Figure 4).

The aforementioned results underscore that the use of DAT with dabigatran may be of benefit even in patients with clinical or procedural complexity factors, as the risk of bleeding seemed to be reduced and the risk of atherothrombotic complications did not seem to be increased compared with TAT.

The AUGUSTUS trial results showed apixaban superiority compared with VKA, as well as placebo superiority compared with aspirin administration regarding safety outcomes, and non-inferiority regarding efficacy outcomes in AF patients undergoing PCI.17 A subgroup analysis, dedicated to complex PCI patients, has not been released yet. The latter is also true for the ENTRUST-AF PCI trial, evaluating edoxaban, which reached the conclusion that DAT with edoxaban was non-inferior to TAT with VKA, regarding primary bleeding outcome, with similar rates of ischemic complications.18

Nevertheless, Alkhalil et al., in their observational study including 256 patients under oral anticoagulation undergoing PCI with bioabsorbable polymer drug-eluting stent implantation, reported that patients with complex anatomy treated with DAT had a higher rate of major adverse cardiovascular events compared with TAT (HR 3.66; 95% CI [1.07–12.47]; p=0.038). Of note, the observed difference was mainly driven by rates of unplanned revascularizations (13.2% versus 0%, p<0.001), while there was also a numerically higher rate of spontaneous MI in patients receiving DAT (7.9% versus 1.4%, p=0.16) with no difference in rates of cardiovascular death.19

In summary, as patients with AF undergoing complex PCI are a high-risk subset of patients, carrying an increased thrombotic and bleeding risk, the aforementioned trials and subgroup analyses provide evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of DAT approach, with a non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant and P2Y12 inhibitor, compared with TAT. Nevertheless, it should be noted that both the PIONEER AF-PCI and RE-DUAL PCI trials were underpowered to identify small, but potentially important, differences in major adverse cardiovascular events rates, and especially to ascertain effects on rare events, such as ST. Even further, as trials were not focused solely on the subgroup of AF patients undergoing complex PCI, the analysis of results regarding efficacy endpoints should be interpreted with caution.

Thus, with the concern of a potentially numerically higher rate of ST or MI in patients receiving DAT, as observed in some trials, the administration of TAT for a short period after index PCI might provide a safer approach toward the prevention of short-term ischemic events, with the caveat of higher bleeding risk. Of importance, even if a DAT approach is adopted at discharge, it should be noted that in the aforementioned randomized trials, most, if not all, patients received TAT, with aspirin, in the peri-interventional vulnerable phase and until randomization. Further studies are required to answer numerous considerations, as physicians have to find the optimal combined antithrombotic regimen, according to the clinical setting (ACS or elective PCI) and patients’ thrombotic–bleeding equilibrium, along with complexity of the disease.

Duration of Treatment

In the absence of specific guideline suggestions regarding patients receiving OAC undergoing complex PCI, decisions regarding the duration of antithrombotic treatment in AF patients undergoing complex procedures are based mostly on atherothrombotic and bleeding risk stratification, as in the cases of non-complex PCI. Although increased ischemic risk is well established in cases of complex PCI, the reckoning of bleeding risk is also an important factor in decision-making, as patients receiving OAC undergoing PCI are also at high bleeding risk, according to Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk classification.20 Various risk scores, although not validated in our specified subgroup of patients, such as PRECISE-DAPT (PREdicting bleeding Complications in patients undergoing stent Implantation and SubsequEnt Dual AntiPlatelet Therapy) or HAS-BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile international normalized ratio [INR], Elderly [>65 years], Drugs/alcohol concomitantly) may also guide decision-making regarding both the type and the duration of antithrombotic treatment regimens.21,22

North American guidelines highlight that, although DAT is suggested as the preferred antithrombotic therapy in most patients with AF undergoing PCI, TAT for up to 1 month after PCI should be considered in selected patients at high ischemic and low bleeding risk.23 Procedural factors, such as stent undersizing, stent underdeployment, small stent diameter, greater stent length, and bifurcation stents, are some of the factors considered to the increase risk for atherothrombotic complications, and thus, could favor a longer duration of TAT.24 As far as American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines are concerned, TAT, when used, is suggested for as short as possible, confined to a 4–6-week duration after index PCI, when the risk of ST is high, whereas DAT with clopidogrel or ticagrelor is an alternative option to reduce the risk of bleeding (class IIa recommendation).25

European guidelines regarding the management of patients with chronic coronary syndromes recommend TAT for 1–6 months in patients with high-risk features for ST, such as left main or proximal left anterior descending artery stenting, last remaining patent artery, suboptimal stent deployment, stent length >60 mm, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, bifurcation with two stents implanted, treatment of a chronic total occlusion, or previous ST on adequate antithrombotic therapy.26 However, in the recently published European guidelines regarding the management of ACS in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation, TAT is recommended only for a short peri-interventional period up to 1 week post-index PCI (class Ia recommendation), whereas in patients at high ischemic risk, the extension of TAT up to 1 month should be considered (class IIa recommendation). Such cases include patients with complex CAD and at least one additional factor, either clinical (diabetes, history of recurrent MI, multivessel CAD, polyvascular disease, premature or accelerated CAD, concomitant systemic inflammatory disease, chronic kidney disease) or technical (implantation of ≥3 stents, treatment of ≥3 lesions, implanted stent length >60 mm, history of ST under antiplatelet treatment, left main stenting or bifurcation with two stents implanted, chronic total occlusion or stenting of last patent vessel).27

TAT for only a short peri-interventional period, followed by dual therapy with OAC and a P2Y12 inhibitor for 6 and 12 months in CCS and ACS patients, respectively, is also recommended in the 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of AF (class Ia recommendation). Prolongation of TAT for up to 1 month is suggested in selected cases when the risk of ST outweighs the bleeding risk (class IIa recommendation), with PCI of the left main stem or last remaining patent artery, suboptimal stent deployment, stent length >60 mm, bifurcation PCI with two stents implanted, treatment of chronic total occlusion, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and previous ST on adequate antithrombotic therapy considered as risk factors for ST.28

P2Y12 Receptor Inhibitor of Choice

Potent P2Y12 receptor inhibitors, namely prasugrel and ticagrelor, are preferred over clopidogrel in the setting of an ACS when there are no contraindications.29 Additionally, they can be administered in specific high-risk situations of elective PCI, such as complex left main stem or multivessel PCI.26 However, in cases where there is a concomitant need for anticoagulation, clopidogrel is preferred as part of a triple therapy scheme, due to the lower risk of bleeding complications.25,30 Indeed, both ticagrelor and prasugrel as part of a TAT regimen have been associated with increased risk of bleeding compared with clopidogrel.31–33 A meta-analysis of three randomized controlled trials regarding the efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in more than 5,600 patients requiring treatment with antiplatelet plus OAC, demonstrated that patients on DAT with ticagrelor had an increased risk of clinically major bleeding compared with those on DAT with clopidogrel (OR 1.52; 95% CI [1.12–2.06] and OR 1.7; 95% CI [1.24–2.33], respectively).31 The increased bleeding risk of using a more potent P2Y12 inhibitor as part of DAT was also confirmed in a recent meta-analysis of more than 22,000 patients with AF on OAC undergoing PCI, where the use of ticagrelor (RR 1.36; 95% CI [1.18–1.57]) or prasugrel (RR 2.11; 95% CI [1.34–3.30]) was correlated with increased bleeding events compared with clopidogrel; of note, bleeding rates were similar between ticagrelor and prasugrel groups (RR 0.80; 95% CI [0.47–1.36]).32

According to current recommendations, European Society of Cardiology guidelines suggest that ticagrelor or prasugrel may be used as part of DAT, as an alternative to TAT with OAC, aspirin, and clopidogrel, in patients with moderate or high risk for ST (class IIb recommendation), whereas a North American expert consensus states that although clopidogrel is the P2Y12 receptor inhibitor of choice, ticagrelor may represent a reasonable treatment option in patients with low bleeding and high ischemic risk as part of a DAT regimen, as tested in the RE-DUAL PCI trial; the use of prasugrel is not encouraged.23,26,27

Conclusion

Population aging leads to an increasing prevalence of AF and complex PCI procedures in everyday clinical practice, emphasizing the imperative need to identify the optimal combination of antithrombotic drugs for the management of this high-risk subset of patients – those with AF undergoing complex PCI. With a view to maintain the subtle balance between ischemic and bleeding complications, DAT seems to be of benefit in terms of bleeding risk mitigation while not significantly compromising efficacy. Nevertheless, due to the increased ischemic risk associated with complex PCI cases, TAT of a short duration, confined to 4 weeks post-index procedure, could represent a more reasonable option, as supported by both European and US published guidelines, especially in cases where angiographic complexity coexists with clinical ischemic risk enhancers, such as diabetes, peripheral artery disease, or chronic kidney disease.