“You can’t really know where you are going until you know where you have been.”

– Maya Angelou1

Cardiogenic shock (CS) is a state of end-organ hypoperfusion and dysfunction, often complicated by a systemic inflammatory response, due to insufficient cardiac output despite adequate preload, secondary to left ventricular, right ventricular, or biventricular dysfunction. CS typically occurs in the setting of acute MI or acute decompensated heart failure, with or without cardiac arrest, and accounts for nearly 15% of all cardiac intensive care unit admissions.2 Inpatient mortality rates, once as high as 90%, remain elevated near 50% despite several decades of advances in pharmacological and device-based therapies, highlighting multiple unmet needs and unachieved goals in the diagnosis and management of this deadly condition.3

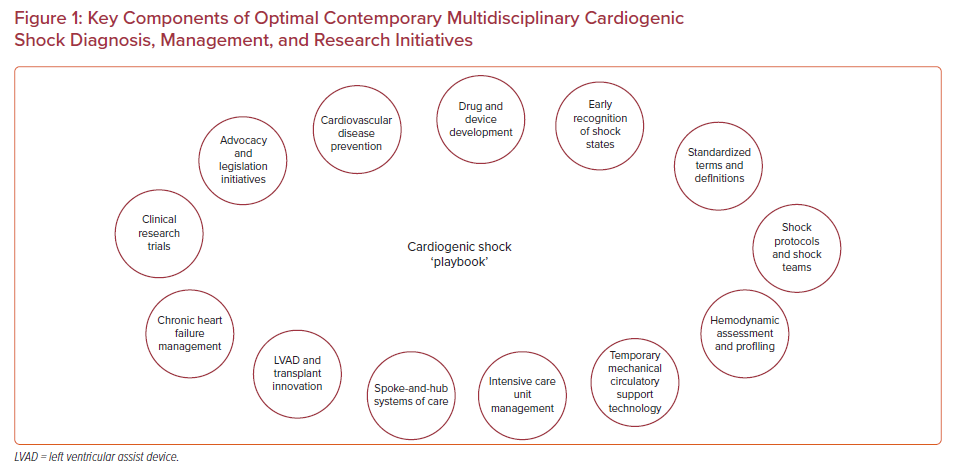

Complex, multidimensional, and resource-intensive problems, such as CS, typically require an organized approach to diagnosis, treatment, monitoring, and recovery. Due to the highly time-sensitive morbidity and mortality of CS, diagnosis and therapies must also be expeditious. A CS ‘playbook’ (Figure 1) may, therefore, aid individuals and teams to: visualize targets, identify capabilities and gaps, articulate critical elements for success, and distill strategies down to actionable component tasks with clearly defined individual and group roles and responsibilities to achieve desired end goals.4

“Shock is the manifestation of the rude unhinging of the machinery of life.”

– Samuel V Gross5

The complexities of the shock syndrome, delays in illness recognition, inconsistencies in phenotype and severity definitions, barriers to access to potentially disease-modifying interventions, and undesired heterogeneities of care both within and between medical facilities all likely contribute to the persistent lethality of CS.6 The presence of multiple converging paths to death with both shock-related and shock-independent factors – to include age, cardiac arrest, organ failure, anoxic brain injury, and bleeding – also further complicate efforts to reduce disease morbidity and mortality.

In this special collection of US Cardiology Review, published contemporaneously with the multidisciplinary international SCAI Shock 2021 Virtual conference (https://scai.org/shock), a collection of worldwide multispecialty experts address the optimal contemporary ‘playbook’ for CS prevention, diagnosis, management, and research to include: advocacy and legislative initiatives, drug and device development, diagnostic frameworks and modalities, therapeutic technologies, multidisciplinary systems of care, cardiac intensive care unit management strategies, rescue and replacement innovations, ongoing clinical research efforts, and future outlook for the field.

“Without good data, we’re flying blind. If you can’t see it, you can’t solve it.”

– Kofi Annan7

Therapeutic decision-making, and appropriate drug and device selection are influenced by pre-shock cardiovascular state, extracardiac comorbidities, shock etiology and phenotype, severity of illness, and the presence or absence of concomitant respiratory failure and/or cardiac arrest. There remains much uncertainty regarding the appropriate definitions, identification, and optimal management of different etiologies, phenotypes, and stages of CS – to include appropriate targets of metabolic tissue perfusion and pump function, and preferred modalities, combinations, and sequence of pharmacological and device-based therapies.8

Shock states often encompass intersecting acute MI, acute decompensated heart failure, post-cardiotomy, pulmonary embolism, cardiac arrest, and valvular heart disease-related entities with etiology-specific risk-related classifications and invasive hemodynamic profiles. Understanding the relationships between disease acuity and severity, hemodynamic phenotypes, age, extracardiac organ involvement, and underlying comorbidities and pre-existing chronic illness, while challenging, is key to successful management.

As shock is a rapidly evolving condition, full-spectrum management requires vigilance and an “unblinking eye” approach to monitoring and therapy across an often prolonged and highly dynamic clinical course. Optimal tailored care necessitates constant hemodynamic situational awareness guided by serial measured and derived hemodynamic parameters to frequently profile and repeatedly re-profile shock states to track clinical trajectories, and guide appropriate weaning and escalation of therapies.9 Optimal management additionally requires detailed and systematic assessments of non-cardiac organ systems, balancing the risks and benefits of individual medical investigations and interventions, while simultaneously surveilling, preventing, and managing the many complications associated with critical illness.10

“Coming together is the beginning. Keeping together is progress. Working together is success.”

– Henry Ford

Patients in CS often deteriorate rapidly, and as shock persists, end-organ hypoperfusion, ischemia, and acidosis worsen, often irreversibly. Successful diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making must, therefore, be both timely and rapidly effective. Use of newer advanced therapies and various forms of mechanical circulatory support often require the coordinated efforts of multiple medical specialists – to include interventional cardiologists, cardiothoracic surgeons, advanced heart failure specialists, and cardiac intensivists.

Multidisciplinary team-based, protocol-driven CS care has demonstrated promising potential to improve clinical outcomes beyond the historical 50% glass ceiling of the past three decades.11 Despite recent consensus efforts to standardize definitions, the complex hemodynamics and variable clinical phenotypes of the CS syndrome mean that the diagnosis and management of CS remains challenging, and often requires expertise across a range of medical specialties.12 Modern multidisciplinary CS teams are designed to enhance the individual strengths of component team members, streamline care delivery, and reduce care variability and disparities to optimize outcomes for these medically complex and resource-intensive patients. The Venn diagram of optimal management thus lies at the crossroads of multiple collaborating cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular specialists working together as a “team of teams.”

At the regional level and beyond, it is critical that big and small community hospitals, academic medical centers, and health systems partner for early identification and stabilization of CS patients with expedited follow-on consultation and/or transfer for definitive management. Intra- and interinstitutional case and process reviews are critical to identify successes, failures, opportunities for improvement, and specific tasks and timelines to become continuously learning and improving organizations.

“Look to the future because that’s where you’ll spend the rest of your life.”

– George Burns

Five key treatment objectives have been increasingly promoted in the acute management of CS: circulatory support, ventricular support, myocardial perfusion, decongestion, and prevention and management of extracardiac critical illness. Although the optimal recipe for successful management of acute MI and acute decompensated heart failure CS remains to be discovered, thus far the “playbook” appears to be: appropriate patient selection and triage, hemodynamically guided diagnosis and treatment, dynamic management algorithms and protocols, combined pharmacological and device therapies, and collaborative multidisciplinary team-based cardiac intensive care unit care.13

Beyond initial stabilization and management strategies, we must continue to pursue ongoing innovations in chronic heart failure pharmacological therapies, as well as temporary and durable ventricular assistance and heart transplantation to maximize heart recovery, reduce symptoms, prevent sudden cardiac death, and provide feasible options for non-recoverable patients.14,15 There is also a parallel need for legislative efforts to develop structured local and regional shock care networks with a tiered model for care delivery for this sickest population of cardiac patients.16

While clinical trials that evaluate drugs, devices, and best practices for CS have been challenging to conduct and slow to enroll, they remain critically important to scientific progress. Barriers to generating high-quality evidence include: non-standardized definitions of CS, heterogeneity of study inclusion criteria, the rapid lethality of CS and associated time-sensitivity of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, multiplicity of pathways to death, overlapping interactions of technologies and systems of care, and difficulties in achieving informed consent in emergency conditions and situations. Looking forward, we must continue to work collectively to overcome these barriers to generating high-quality evidence.3,17 Although the journey may be long, the destination is vitally important to us all.