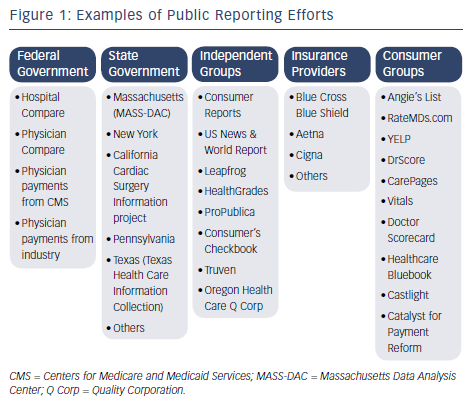

In what is often cited as the earliest public reporting of healthcare information, Florence Nightingale published mortality rates at British military hospitals caring for casualties of the Crimean War.1 Dr Ernest Codman, about 50 years later, called for the public release of surgical outcomes at his hospital, but was highly criticized for his effort eventually leading to the loss of his hospital privileges.2 His early efforts, however, contributed to the founding of the American College of Surgeons and later The Joint Commission. The next major public reporting effort occurred in the late 1980s when the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) published risk-adjusted death rates in US hospitals.3 Although not intended for public release, these reports eventually became public and were the subject of considerable criticism.4 Although imperfect, the HCFA experience stimulated development of other quality improvement registries and statewide reporting systems for coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) outcomes.5,6 With the implementation of the “Hospital Compare” website in 2002, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) revived public reporting of data from Medicare beneficiaries aggregated at the hospital level.7 More recently, CMS began reporting on group and individual physician performance.8 Public reporting programs now exist in many forms, including: a) federal and state initiatives; b) reports from payers and business consumer groups; c) reports from independent organizations that use their own proprietary analysis and rating schemes; and d) reports focusing on the cost of care.9–12 Public websites also exist where patients can report their anecdotal experiences with physicians without any opportunity for physician rebuttal of their comments see Figure 1.13

Rational for Public Reporting

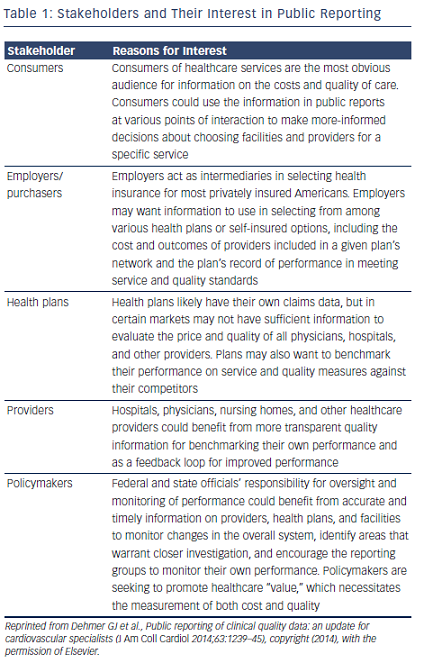

Although there are many outstanding characteristics of the US healthcare system, it also has many shortcomings. Unacceptable gaps in care and concerns over quality issues are increasingly identified in the public domain. With the current national emphasis on quality improvement, accountability and cost-effectiveness in healthcare, stakeholders such as government agencies, purchaser and provider organizations, and consumers are seeking information to inform decisions about healthcare facilities and providers see Table 1. Some advocates would even state that public reporting is a professional ethical responsibility.14 The most persuasive justification for public reporting is the public’s right to know about the care they are likely to receive from hospitals and physicians. Public reporting is sustained by the belief that accessible, transparent, quality information will affect decisions and behaviors of the various stakeholders, ultimately resulting in an improvement in healthcare delivery and outcomes. Transparency encourages patient autonomy by providing patients with information that should allow them to make better-informed decisions about their healthcare choices. However, for this to succeed the reporting process must be accurate and fair.

Moving forward, there is also a clear mandate to begin changing reimbursement models so they are based on the quality and value of care, rather than the quantity of care. For that to succeed, quality measures that are meaningful and validated must exist. Employers continue to allocate an increasing portion of their budget for the provision of healthcare benefits to their employees similar to what the federal government has experienced for Medicare beneficiaries. This increasing financial burden on employers has several effects. It results in employees saddled with a greater percentage of their healthcare cost and, as that occurs, patients become more conscious of the care they are receiving. Insurers are pressured to provide lower cost, higher value products and ultimately this translates into pressure on providers to demonstrate the quality and value of their care. To remain competitive, healthcare systems and providers must then accelerate their quality improvement efforts.

Public reporting of physician, health plan, and institutional performance is being leveraged in an attempt to steer patients to the best performing providers and facilities on the assumption that patients will receive better and more cost-effective care. The public release of performance data has been proposed as a mechanism for improving the quality of care by providing more transparency and greater accountability of healthcare providers.15 However, there are data showing that areas with comprehensive, but confidential, data reporting had improvements in outcomes similar to those in public reporting states and that public reporting added to existing confidential feedback reporting resulted in little incremental improvement in outcomes.16–18 Moreover, the use of publically reported information by various segments of the population is variable and the impact of this information on patients’ decision-making is uncertain.19,20 Rather than identifying the absolute best hospital or provider in the country, patients’ seem more focused on access to empathetic, interactive providers and the availability of local services for common conditions that meet an acceptable standard of care.21

Public Reporting of Cardiovascular Data

Public reporting developed in the cardiovascular arena well before many other areas of medicine. Beginning in the mid-1990s, New York and Pennsylvania started publicly reporting outcomes from cardiac surgery followed by similar programs in Massachusetts and California.22–25 Several of these same states now have analogous programs for publically reporting PCI data.26,27 In 2005, an independent group of seven New England hospitals started collecting data for patients undergoing several cardiovascular procedures and began providing a public report of CABG results on their website.5 More recently, the Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program (COAP) program was launched in the State of Washington reporting both CABG and PCI outcomes.28 Cardiovascular professional organizations have also joined the growing public reporting effort. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) has maintained a clinical database on cardiac surgical procedures since 1989 and in 2011 began a voluntary public reporting program that has been well received.6,14,29 Likewise, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) recently launched a public reporting program using clinical data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry.30,31

Benefits of Public Reporting

Public reporting is intended to improve healthcare delivery and patient outcomes and studies showing the positive impact of public reporting are emerging. For example, the use of aspirin prophylaxis was 95 % in a state where this metric was publically reported compared with much lower aspirin use in a large national survey.32,33 Likewise, data from the Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality shows increases in quality performance when data from groups are displayed publically on a website.34 Survey data from administrators and providers endorse the benefits derived from public reporting such as a greater involvement of leadership in performance improvement, creation of a sense of accountability to internal and external customers, improved awareness of performance measure data throughout the hospital, and a stronger focus on organizational priorities.35 The STS has recently published their 4-year experience since beginning their public reporting program.36 Facility participation in public reporting varied from 22 % to 46 % during their reporting periods. Risk-adjusted, patient-level mortality rates for isolated CABG were consistently lower at public reporting versus nonreporting sites and reporting centers had higher composite performance scores and higher mean annualized CABG volumes than non-reporting sites. Importantly, no evidence of risk aversion was found.

However, systematic reviews of public reporting programs note that rigorous evaluations of many major public reporting programs are lacking.37,38 These reviews cite some evidence that publicly releasing performance data stimulates quality improvement activity at the hospital level, but also conclude that the overall the effect of public reporting on effectiveness, safety, and patient-centeredness remains uncertain. Even less data are available to show a benefit from the public reporting individual or group data.

Pitfalls of Public Reporting

Several potential problems are often cited related to public reporting efforts. First, data used in public reporting are derived from either administrative or clinical data sets. Administrative, financial (claims), and other descriptive data are readily available and thus attractive sources of information, but are only surrogates for clinical data. Several studies have shown that administrative data are: a) payer and market specific; b) use old and sometimes nonactionable data; and c) may poorly reflect the severity of illness, correct diagnosis, and clinical outcomes.39–41 For example, in two separate studies that compared cardiac surgery performance using administrative versus clinical data sources there were substantial inconsistencies in the comparisons leading to the conclusion that report cards using administrative data are flawed compared with those derived from validated clinical data.42,43

Clinical registry data have several advantages over administrative data.39,40,43 Clinical data more directly mirror the clinical care received by patients and thus are more representative of actual performance than data derived solely from claims. Administrative data frequently have a lag time of 2 years whereas clinical data are timelier and thus provide an excellent source of nationally benchmarked data to providers. Receiving timely data allows providers to construct better quality-improvement activities with feedback available soon after subsequent data submissions. Furthermore, data submission to clinical registries can be incorporated into provider workflow, thus potentially reducing the burden of data collection. Clinical data from registry programs also can be used for research or educational programs that focus on quality improvement.

Second, concern has been expressed that public reporting programs may lead to unintended consequences that could offset their benefits.44,45 The majority of these reports highlight the development of risk-adverse behavior among physicians and facilities subject to public reporting. One of the earliest examples of this behavior was observed after New York State started publishing mortality related to CABG surgery. Following the release of these data, there was a reduction in risk-adjusted CABG mortality resulting in the impression that the public reporting program was highly successful. However, a different perspective emerged when referrals from New York to the Cleveland Clinic were examined after public reporting began in New York.46 Patients referred from New York had a worse risk profile and a higher expected mortality rate than other referrals. The authors speculated that the beginning of public reporting in New York likely triggered the referral of high-risk patients out of state, explaining the reduction of CABG mortality in New York. A similar experience was reported related to the public reporting of CABG outcomes in Pennsylvania.47

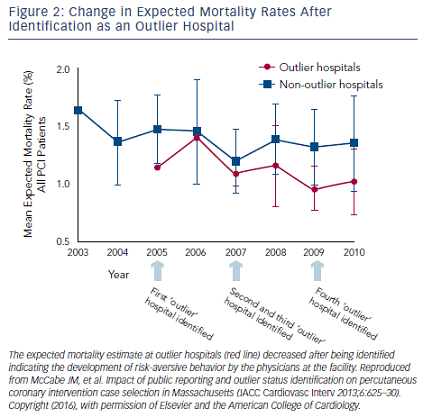

Public reporting of PCI data has a shorter history compared with that of cardiac surgery, but similar trends in physician behavior are being observed. Compared with New York, which has public reporting of PCI mortality, patients in Michigan, which does not have public reporting, more frequently were treated with PCI for acute MI (14.4 % versus 8.7 %) and cardiogenic shock (2.56 % versus 0.38 %) and had a higher prevalence of congestive heart failure and extracardiac vascular disease.48 The unadjusted in-hospital mortality rate was lower in New York than in Michigan reflecting the exclusion of high-risk patients, but there was no significant difference in mortality between the two states after adjustment for comorbidities. The authors concluded that the lower use of PCI among these higher-risk patients in New York was likely related to physician concerns over being identified as an outlier in a public report. In a separate study, patients from New York presenting with cardiogenic shock were less likely to receive angiography, PCI, or CABG compared with patients from other states.49 These patients experienced an in-hospital mortality 1.5 times higher, suggesting that life-saving treatments were being avoided in this high-risk group in an effort to elude identification as an outlier in a public report. Survey data from New York physicians confirmed this, with 83 % of practitioners agreeing that patients who were at high risk were denied PCI because of fear of public reporting and 79 % confirming that their own decisions on performing PCIs was influenced by a fear of public reporting.50 Similar concerns were raised about the public reporting of PCI data in Massachusetts and indirectly confirmed by examining the risk profile of patients undergoing PCI at hospitals after the facility was identified as an outlier in a public report.51,52 After being publically identified as an outlier, the risk profile of PCI patients at the institution became significantly lower compared with non-outlier institutions (see Figure 2). This observation implies the presence of risk-aversive behaviors among PCI operators at these outlier institutions as an unintended consequence of public reporting.

Third, risk-adjustment methods currently available are suboptimal and may not include all relevant variables. To minimize risk-avoidance behaviors, some reporting efforts now specifically exclude extremely high-risk and salvage patients. In the Massachusetts PCI registry, a “compassionate use” data element has been added to capture these types of cases.53 It has also been suggested that mortalities be adjudicated to determine if they were truly procedure related or related to the natural history of a disease process. This recommendation is supported by the fact that after further blinded review, about 80 % of the mortalities at one Massachusetts hospital were felt to not be directly related to the procedure and more related to the natural history of disease in the patient.51 Payers are often focused more on cost profiling physicians, but the accuracy of these methods have also been questioned.54

Finally, the manner in which information is presented in some public reports is overly complex and can be confusing to consumers. Everyone desires transparent and accurate reporting presented in a fair and understandable format. The information provided in public reporting should be understandable and usable. The amount of, and manner in which, information is displayed determines whether consumers can actually process and use it in decision-making.55,56 Information displays that aid consumers in quickly understanding the meaning of data increase consumer motivation to use the information in contrast to a bewildering display that will quickly be dismissed as too complicated.

Public Reporting in the Future

With the current national emphasis on quality measurement, accountability, transparency, and value-based purchasing, stakeholders and consumers of healthcare are eager to obtain information about healthcare facilities and providers. This has created a rich environment for public reporting that, at present, is uncoordinated, often perplexing to patients, and further confused by divergent public rankings of the same facility in different reporting systems.57,58 Despite this, the public release of information about the performance of healthcare systems and individual providers continues to grow, although it lags behind the reporting of commercial products and services in many other industries. Hospital-level public reporting in its various formats is now familiar to most clinicians with individual provider reporting becoming more prevalent. Physician-level reporting has additional challenges. Attributing process and outcome of care metrics to a single provider when patients interact with multiple different providers during an encounter can be difficult. Moreover, determining if differences in outcomes are statistically significant becomes more difficult when the number of patients treated for a specific condition at a facility is divided among multiple providers.

Passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 created a new framework by mandating a national strategy for quality improvement, including public reporting of health quality information. More recently, the Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2015 (known as MACRA) incorporates a merit-based incentive payment system that will encourage alternative payment models compared with the traditional fee-for-service model. Payment adjustments will be based on performance in four categories (clinical quality, meaningful use, resource use, and clinical practice improvement) creating an environment with many additional public reporting opportunities, but with an unproved impact on access and quality or care.

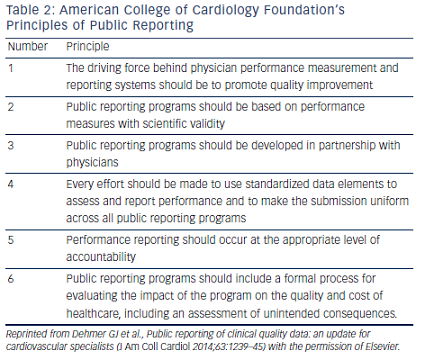

Professional organizations including the ACC and the STS have articulated the main principles to guide public reporting initiatives (see Table 2).59,60 Although there are challenges to developing accurate and meaningful public reports, a thoughtful, measured public reporting program using clinical data with transparent and scientifically sound methodology, and oversight by professional organizations, has benefits and can minimize the potential unintended consequences. Providing these data demonstrates a good faith effort to deliver high-quality information to assist patients’ healthcare decisions. Value-based purchasing will be dominant in several years and will include public access to provider performance. Failure to understand and use clinical data to improve operations now may result in facilities facing unfair public judgments based on administrative or proprietary-derived data and falling behind in their adaptation to the changing healthcare environment.61

The medical community continues to have concerns over the unintended consequences of public reporting and the ability of patients and other stakeholders to misuse or misinterpret the results. By voluntarily reporting results based on the best available data and analytics public reporting has the potential to enhance a healthcare facility’s standing and linkage to their community. The public reporting of healthcare outcomes exists now and will only expand into the future as the public becomes more engaged in the quality and cost of their healthcare.